On the Balcony

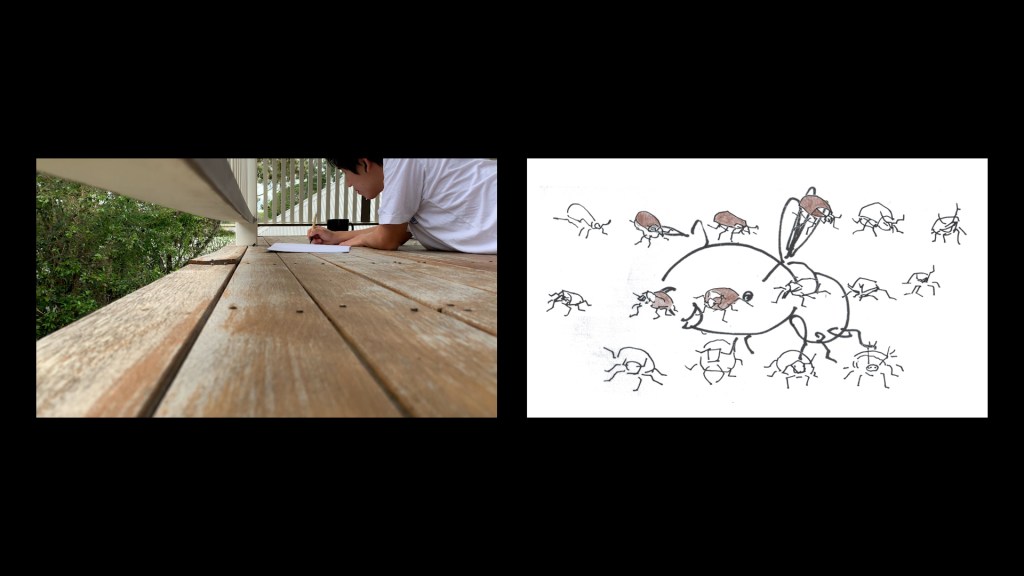

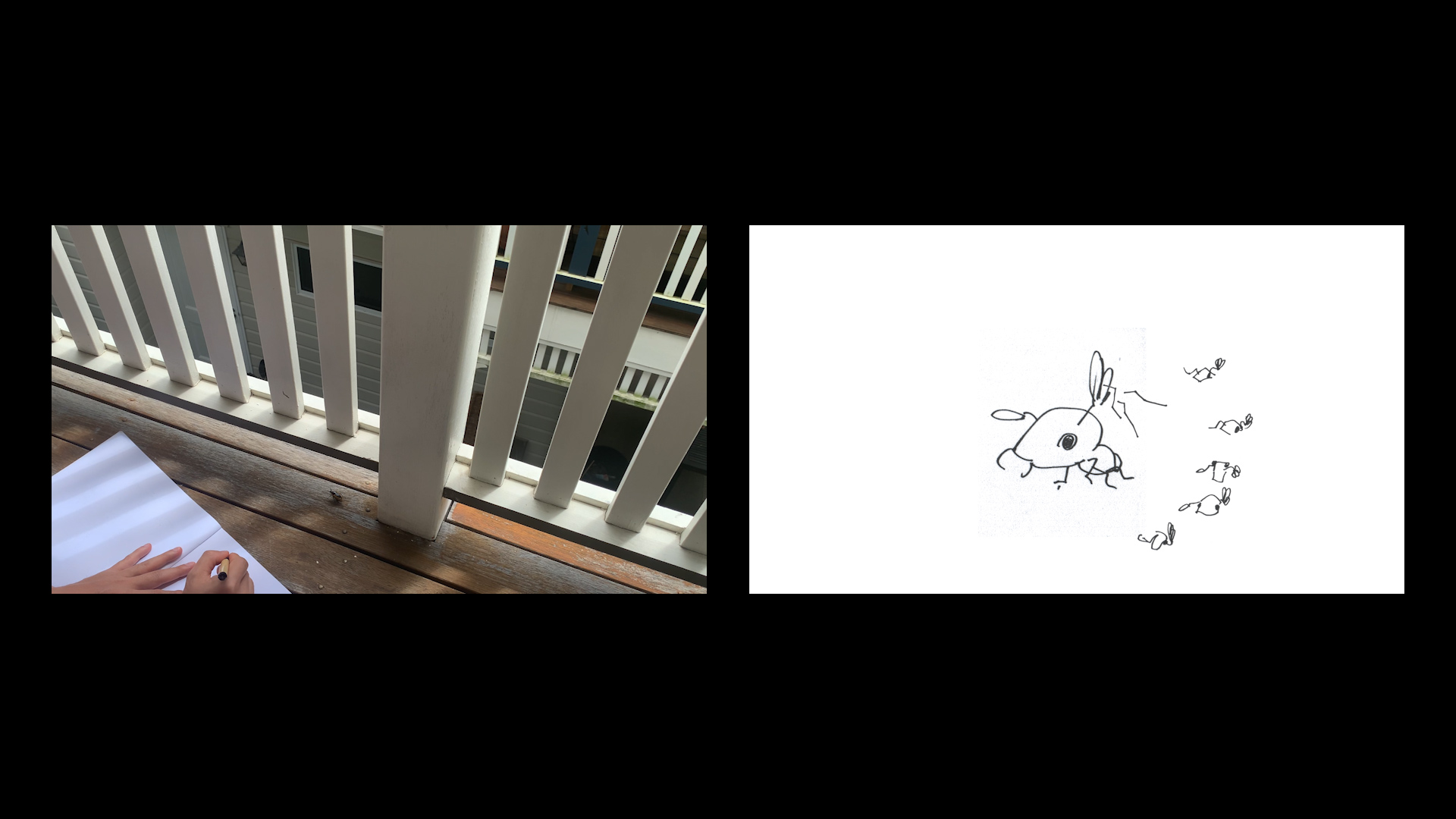

Synopsis: Lately, I spent a few hours every morning on the balcony at my house on Spring Street. Reading, stretching and getting the sun. I just noticed there were little insects coming and going time after time. I put a pen and a small notebook beside my mat so when any comer stopped by, I could spend some time interacting with them. I noticed that I felt calmer than before. The anxiety of missing catching moments was gone. I realised that when one is gone, the other one will come. I will have a next chance when the time comes.

Technique: Pen, pencil, colour pencil on paper

Year: 2024

Spectator and Attention

“Every mundane object was worth our wondering contemplation.” (Leonard, 1995, pp. 120)

Historical research shows that in the first half of the 19th century, artistic spaces such as performing arts venues, music venues, and play theatres, were not predominated by silence and self-restraint yet (Laermans, 2007, p. 236). The mindful attention was gradually imposed to contemplate the deeper meanings of a work of art by the new urban bourgeois elite (ibid). In order to realise aesthetic experience, read a meaning, or decode a message, the spectators ought to become silent and attentive, so they can transform themselves into an audience. These changed the spectators’ bodily and emotional involvements, such as booing, interim applause, or loud encouragement during artistic events, including cinema theatre.

To become a spectator of cinema, the spectator cannot just simply watch films, but need to take them seriously (Fuery, 2004, p. 9). In Cinema and Madness (2004), Patick Fuery discussed the relations between cinema and spectators through Foucault’s work on madness. In short, madness here was mentioned as the disordered and seductive formation and function of cinema, operated through meaning, knowledge, and subjectivity within the spectator. Cinema produces images that are unique to its qualities, and its representation is never simple and rarely transparent. The spectator is confronted with something as resistant to representation as madness is. The representational processes construct signs that narratives can develop, and the spectator can make sense of the structure (Fuery, 2004, p. 15). The spectator attempts to narrativise the madness, making it part of the cultural events and attitudes, current social order, and consciousness, using unreason to construct reasoning.

At this point, I applied ‘Zeuxus and Phidias: Idealism’s Two Principal Parables’ in the art of everyday objects and the art of commonplace (Leonard, 1995) to this work in order to blend the information showed on screen with the daily life experience. The parables reflect two schools of thought within idealism. Zeuxis’s method (an Ancient Greek painter) is to select and compose an object’s higher beauty from nature instead of relying entirely on an imagined image. Something not to be imagined but to be discovered by comparing natural examples. In another parable, Phidias’s method (an Ancient Greek sculptor, painter) disdains and ignores completely to look at everyday objects. Phidias worked entirely from an interior image, not to select beauties from nature. The sublime notion of beauty lives in our minds. Therefore, when the spectator is aware that the moving image maker’s power is fundamentally exercised through selection, distribution, and deformation of materials, their attempt to narrativise the madness of cinema might be less complicated and more straightforward.

Back to ‘On the Balcony’, the work simultaneously displays two screens: one is the time of making process, or to be more accurate in this context, the time from nature (Left). Another one is the time of exhibiting, the interior images in my mind executed visually (Right). This work intends to let the spectator watch and compare the selected materials displayed on screen, and operate through meaning, knowledge, and subjectivity within the spectator. The spectator confronts this simple work under the inevitable madness of the formation and function of cinema.

Reference

Fuery, P. (2004) Madness and cinema: Psychoanalysis, spectatorship, and culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Laermans, R. (2007) ‘The politics of collective attention’, Knowledge in motion, pp. 235-242, doi: 10.1515/9783839408094-023.

Leonard, G.J. (1995) Into the light of things: Art of commonplace from Wordsworth to John Cage. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Credit

Animation l Thanut Rujitanont

Sound I Thanut Rujitanont

Supporter l Griffith Film School

Producer l Graphy Animation